From skepticism to success: How AI is helping teachers transform classrooms in Peru

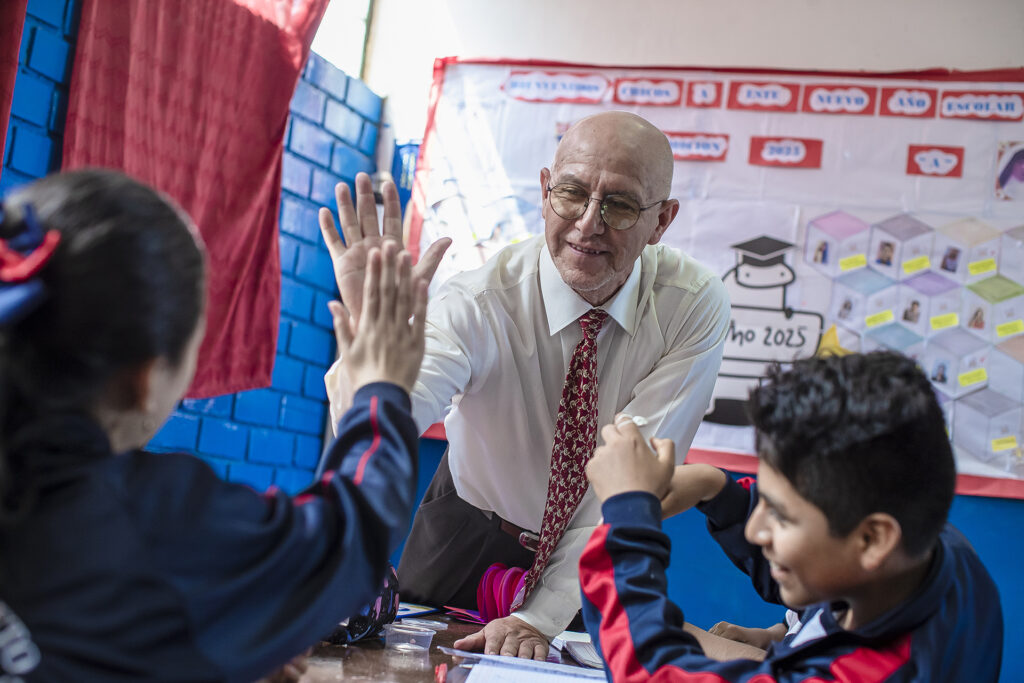

Marco Antonio Pedraza, a sixth-grade primary school teacher who migrated as a young man from the countryside to bustling Lima, used to spend his own money to purchase specialized teaching materials for the three neurodivergent kids in his class. He had only a vague idea of what AI was and was skeptical about its potential.

Then Pedraza was introduced to Microsoft 365 Copilot Chat, the AI companion that helps with work tasks. A group of AI experts recently trained him on how to write effective prompts to quickly generate personalized activities for the students just by typing a few traits of each. He was amazed by the results.

“It was a revelation,” says Pedraza, an experienced public school teacher with a humble background. “These days, a teacher requires technology to effectively assist the kids.”

He says the new tool saves him precious time and facilitates a more personalized education. As he gradually expands its use, he hopes Copilot will enhance the learning experience of all his students while opening new horizons for him that could help him thrive within Peru’s educational system.

Pedraza is one of nearly 500 primary public school teachers participating in a pioneering pilot program launched by the education authorities of Lima metropolitan area (DRELM) in partnership with the World Bank, spanning over 200 public schools. All educators teach fifth and sixth grades. Most of the schools cater to children from low-income families, with some located in the city’s poorest areas.

Local education authorities expect AI can raise education standards and improve teachers’ capabilities in an inexpensive and easily scalable way, says Marcos Tupayachi, the representative of Peru’s education ministry for metropolitan Lima, the country’s capital and one of the largest cities in South America with 10.5 million residents or 30% of Peru’s population.

“It will help us a lot in transitioning from a traditional approach to a much more modern, student-centered approach,” Tupayachi points out.

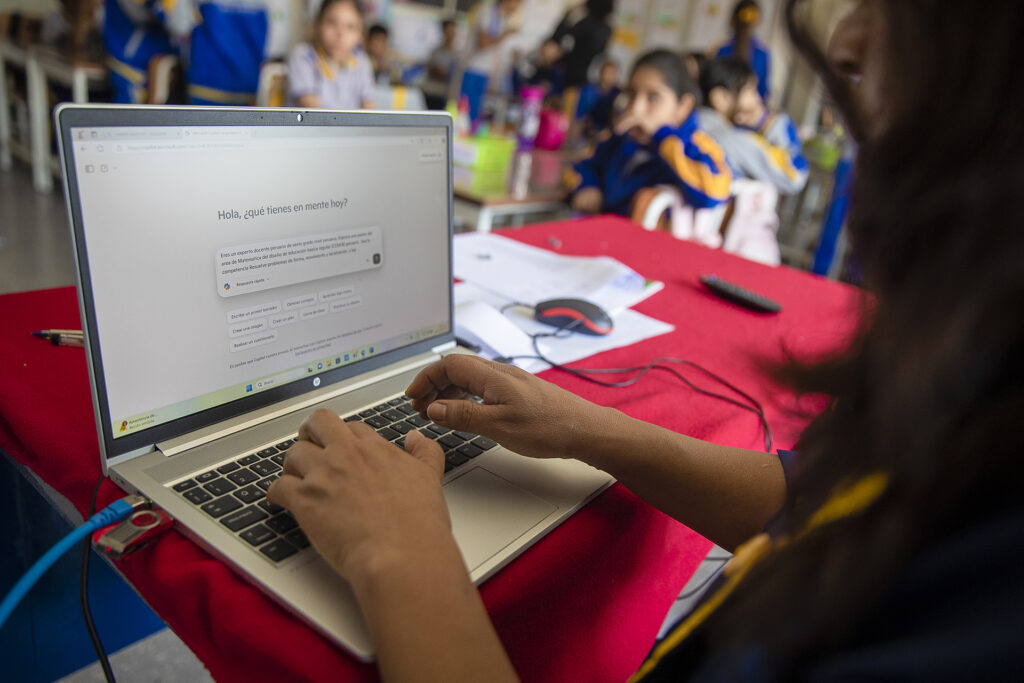

Copilot Chat is powered by the latest AI models and uses web data and files uploaded by users to generate content. After a short training co-designed with a group of primary teachers, participating educators began using it at the start of the school year in early March through accounts provided by Peru’s education authorities. Chats are protected and not exposed to the public or used to train AI models.

If the results are as positive as expected, demonstrating enhanced student learning and improved teacher-student dynamics, the program could be expanded to all primary schools in Lima starting next year, Tupayachi says.

A companion in the classroom

The World Bank is offering technical support to Peru to deploy the program, as part of the group’s wider efforts to promote education and social inclusion across the developing world.

Through AI, teachers can quickly and efficiently create lesson plans, curriculums and learning materials, while supporting grading and other administrative tasks, explains Ezequiel Molina, a World Bank senior economist.

This is especially important in a developing country where public schools are often understaffed and educators are underpaid and face limited training and access to advanced technology, Molina notes.

“We thought AI could be seen as an ally, helping teachers solve their challenges, design better and faster lessons and use the extra time to think about improving the educational experience for students,” he says.

Many educators in Peru have several jobs to make ends meet, says the economist, so AI can decisively help find a balance between work and life. As reliable connectivity is not widely available across schools, many educators in the program use Copilot on their own laptops at home or on their phones. They say they could barely believe the effectiveness of the AI tool when they first tried it.

Marcela Vásquez teaches at a primary public school in a working class, densely populated neighborhood of Lima. She was so afraid of AI that she didn’t even dare to ask what it was. She thought AI was there to replace her.

Her worries vanished the moment she typed her first prompt during the training session. She interacted with Copilot to craft a short story about new kids starting their first day in her class of 30 students.

“It performed phenomenally. I was utterly amazed — it was truly jaw-dropping,” Vásquez shares. She then told the story to her students and engaged them in a discussion on the importance of teamwork and inclusion. The teacher now sees AI as a partner.

In another recent experiment for her math class, Vásquez asked Copilot to create a sketch illustrating the basics of locations and directions. The plan organized students into small groups, guiding them through various areas of the school, such as the library and the courtyard.

Vásquez says the activity was so fun and instructive that the kids were delighted. “This class is so cool!” her students shouted in lockstep, the teacher recalls. The kids were totally engaged in a new experience.

“It gives me fresh ideas, encourages creativity and transforms the class into a lively experience,” Vásquez notes.

Pedraza says Copilot recently generated a highly detailed lesson to explain the different types of polygons and their characteristics, specifically tailored for the three students with cognitive issues. What used to take him 15 days to prepare was now ready in three seconds. “It was as if it had been crafted by an expert,” he says.

Education official Tupayachi is betting educators in Peru will quickly embrace AI. Teachers under the program, he said, “are like children who have been given a new toy.”

Closing educational gaps

Peru faces significant educational challenges. While metropolitan Lima is in far better shape, 7 out of 10 public schools across the country lack at least one essential service, such as clean water, electricity or sewage systems. Some 65% of primary schools in Peru have no internet access, according to the 2023 Peru Education Census.

The World Bank recognizes the challenges posed by low internet access and plans to test how AI can operate in schools with no connectivity, according to economist Molina. The ongoing initiative aims to develop effective solutions for all educational institutions, regardless of their technological infrastructure. In the meantime, teachers are learning how to use AI tools and conduct much of their pedagogical planning from home.

Educators encounter many obstacles as well. A newly hired primary school teacher earns as little as $850 per month, government data shows. Primary classrooms accommodate on average nearly 30 students, compared to between 17 and 22 in the US, according to the US National Center for Education.

In this context, AI can play a pivotal role in bridging educational gaps, Molina notes.

“What one would expect (from the program) is that the quality of the interaction between students and teachers improves, thereby enhancing the quality of teaching and ultimately the learning experience,” he says. He expects to have an impact assessment later this year.

The joint effort between Lima authorities and the World Bank was officially announced in December. A dozen primary teachers from Lima, selected through a contest, collaborated with the organizers to co-create the content and structure of the March training sessions, aiming to address the specific needs of the educators. A separate group of technology-savvy college professors did the training.

Among those was Norma Rodriguez, a technology expert and professor at the Cayetano Heredia Peruvian University. It was not an easy start: some teachers believed AI was a robot; others struggled setting up their Copilot Chat accounts, Rodriguez remembers.

Once teachers were briefed on the basics of AI, they were guided on how to craft effective prompts by being clear and specific — focusing on assigning a role, what the task involves and how it should be executed — while also providing necessary context. They also learned to upload information, such as publicly available educational templates for lesson plans, which Copilot could then leverage.

Trainers encouraged the teachers to think of prompting as akin to following a recipe, with three golden rules in mind for the responsible use of AI: see it as an assistant not a replacement, always verify and improve the generated content and strictly protect the privacy of students.

As they learned how to get great results, Rodriguez says teachers were increasingly elated — even proud of themselves: “They saw that they were still teachers yet reinvented, with opportunities to do things they previously could not do or did not know how to accomplish.”

Vásquez puts it this way: “I feel a better teacher now than I was before.”

Top image: Marcela Vásquez, who teaches at a working-class neighborhood of Lima, was initially afraid of AI. She now sees AI as a partner. Photo by Julio Reaño.